178x Filetype PDF File size 0.60 MB Source: www.mscs.dal.ca

2.2 Free and bound variables, α-equivalence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

2.3 Substitution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

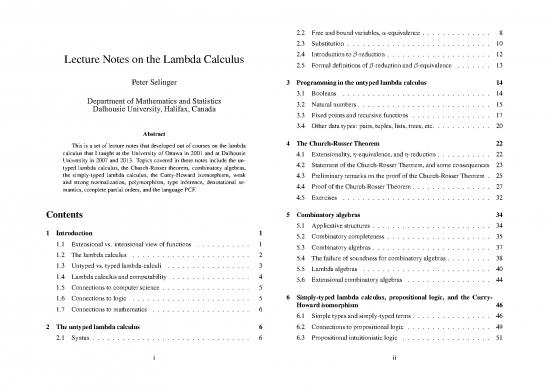

Lecture Notes on the Lambda Calculus 2.4 Introduction to β-reduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

2.5 Formaldefinitionsof β-reductionand β-equivalence . . . . . . . 13

Peter Selinger 3 Programmingintheuntypedlambdacalculus 14

3.1 Booleans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Department of Mathematics and Statistics 3.2 Natural numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada

3.3 Fixed points and recursive functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

3.4 Other data types: pairs, tuples, lists, trees, etc. . . . . . . . . . . . 20

Abstract

This is a set of lecture notes that developed out of courses on the lambda 4 TheChurch-RosserTheorem 22

calculus that I taught at the University of Ottawa in 2001 and at Dalhousie 4.1 Extensionality, η-equivalence, and η-reduction . . . . . . . . . . . 22

University in 2007 and 2013. Topics covered in these notes include the un-

typed lambda calculus, the Church-Rosser theorem, combinatory algebras, 4.2 Statement of the Church-Rosser Theorem, and some consequences 23

the simply-typed lambda calculus, the Curry-Howard isomorphism, weak 4.3 Preliminary remarks on the proof of the Church-Rosser Theorem . 25

and strong normalization, polymorphism, type inference, denotational se- 4.4 Proof of the Church-Rosser Theorem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

mantics, complete partial orders, and the language PCF.

4.5 Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Contents 5 Combinatoryalgebras 34

5.1 Applicative structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

1 Introduction 1 5.2 Combinatorycompleteness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

1.1 Extensional vs. intensional view of functions . . . . . . . . . . . 1 5.3 Combinatoryalgebras . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

1.2 Thelambdacalculus . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 5.4 Thefailure of soundness for combinatory algebras . . . . . . . . . 38

1.3 Untypedvs. typed lambda-calculi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 5.5 Lambdaalgebras . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

1.4 Lambdacalculusandcomputability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 5.6 Extensional combinatory algebras . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

1.5 Connectionsto computerscience . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

1.6 Connectionsto logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 6 Simply-typed lambda calculus, propositional logic, and the Curry-

1.7 Connectionsto mathematics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 Howardisomorphism 46

6.1 Simple types and simply-typed terms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

2 Theuntypedlambdacalculus 6 6.2 Connectionsto propositional logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49

2.1 Syntax . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 6.3 Propositional intuitionistic logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51

i ii

6.4 Analternative presentation of natural deduction . . . . . . . . . . 53 9.2 Typetemplates and type substitutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82

6.5 TheCurry-HowardIsomorphism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55 9.3 Unifiers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84

6.6 Reductions in the simply-typed lambda calculus . . . . . . . . . . 57 9.4 Theunification algorithm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

6.7 AwordonChurch-Rosser . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58 9.5 Thetypeinferencealgorithm . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87

6.8 Reduction as proof simplification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

6.9 Getting mileage out of the Curry-Howardisomorphism . . . . . . 60 10 Denotationalsemantics 88

6.10 Disjunction and sum types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61 10.1 Set-theoretic interpretation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89

6.11 Classical logic vs. intuitionistic logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 10.2 Soundness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

6.12 Classical logic and the Curry-Howardisomorphism . . . . . . . . 65 10.3 Completeness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

7 Weakandstrongnormalization 66 11 ThelanguagePCF 93

7.1 Definitions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 11.1 Syntax and typing rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

7.2 Weakandstrongnormalizationin typed lambdacalculus . . . . . 67 11.2 Axiomatic equivalence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

11.3 Operational semantics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

8 Polymorphism 68 11.4 Big-step semantics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

8.1 Syntax of System F . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68 11.5 Operational equivalence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

8.2 Reduction rules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69 11.6 Operational approximation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

8.3 Examples . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 11.7 Discussion of operational equivalence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

8.3.1 Booleans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 11.8 Operational equivalence and parallel or . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

8.3.2 Natural numbers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

8.3.3 Pairs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72 12 Completepartialorders 104

8.4 Church-Rosser property and strong normalization . . . . . . . . . 72 12.1 Whyaresets notenough,in general? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

8.5 TheCurry-Howardisomorphism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73 12.2 Complete partial orders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

8.6 Supplying the missing logical connectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 12.3 Properties of limits . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

8.7 Normalformsandlongnormalforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75 12.4 Continuousfunctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

8.8 Thestructure of closed normal forms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77 12.5 Pointed cpo’s and strict functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

8.9 Application: representation of arbitrary data in System F . . . . . 79 12.6 Products and function spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

12.7 The interpretation of the simply-typed lambda calculus in com-

9 Typeinference 81 plete partial orders . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

9.1 Principal types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82 12.8 Cpo’s and fixed points . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

iii iv

12.9 Example: Streams . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 1 Introduction

13 Denotationalsemantics of PCF 111 1.1 Extensional vs. intensional view of functions

13.1 Soundnessand adequacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111

Whatisafunction? Inmodernmathematics,theprevalentnotionis that of “func-

13.2 Full abstraction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113 tions as graphs”: each function f has a fixed domain X and codomain Y , and a

function f : X → Y is a set of pairs f ⊆ X × Y such that for each x ∈ X, there

14 Acknowledgements 114 exists exactly one y ∈ Y such that (x;y) ∈ f. Two functions f;g : X → Y are

consideredequalif theyyield the same outputon eachinput, i.e., f(x) = g(x) for

15 Bibliography 115 all x ∈ X. This is called the extensional view of functions, because it specifies

that the only thing observable about a function is how it maps inputs to outputs.

However, before the 20th century, functions were rarely looked at in this way.

Anolder notion of functions is that of “functions as rules”. In this view, to give

a function means to give a rule for how the function is to be calculated. Often,

2

such a rule can be given by a formula, for instance, the familiar f(x) = x or

g(x) = sin(ex) from calculus. As before, two functions are extensionally equal if

they have the same input-output behavior; but now we can also speak of another

notion of equality: two functions are intensionally1 equal if they are given by

(essentially) the same formula.

When we think of functions as given by formulas, it is not always necessary to

knowthe domainand codomainof a function. Consider for instance the function

f(x) = x. This is, of course, the identity function. We may regardit as a function

f : X → X for anyset X.

In most of mathematics, the “functions as graphs” paradigm is the most elegant

and appropriate way of dealing with functions. Graphs define a more general

class of functions, because it includes functions that are not necessarily given by

a rule. Thus, when we prove a mathematical statement such as “any differen-

tiable function is continuous”, we really mean this is true for all functions (in the

mathematical sense), not just those functions for which a rule can be given.

Ontheotherhand,incomputerscience,the“functionsasrules”paradigmisoften

moreappropriate. Think of a computer program as defining a function that maps

input to output. Most computer programmers (and users) do not only care about

the extensional behavior of a program (which inputs are mapped to which out-

puts), but also about how the output is calculated: How much time does it take?

Howmuchmemoryanddiskspaceisusedintheprocess? Howmuchcommuni-

cation bandwidth is used? These are intensional questions having to do with the

1Note that this word is intentionally spelled “intensionally”.

v 1

particular way in which a function was defined. function f and maps it to f ◦ f, the composition of f with itself. In the lambda

calculus, f ◦ f is written as

λx.f(f(x));

1.2 Thelambdacalculus and the operation that maps f to f ◦ f is written as

The lambda calculus is a theory of functions as formulas. It is a system for ma- λf.λx.f(f(x)).

nipulating functions as expressions.

Let us begin by looking at another well-known language of expressions, name- Theevaluationofhigher-orderfunctionscan get somewhat complex;as an exam-

ly arithmetic. Arithmetic expressions are made up from variables (x;y;z...), ple, consider the following expression:

numbers(1;2;3;...), and operators (“+”, “−”, “×” etc.). An expression such as � 2

x+ystandsfortheresultofanaddition(asopposedtoaninstructiontoadd,orthe (λf.λx.f(f(x)))(λy.y ) (5)

statement that something is being added). The great advantage of this language Convince yourself that this evaluates to 625. Another example is given in the

is that expressions can be nested without any need to mention the intermediate following exercise:

results explicitly. So for instance, we write

Exercise 1. Evaluate the lambda-expression

A=(x+y)×z2;

�

(λf.λx.f(f(f(x))))(λg.λy.g(g(y))) (λz.z +1) (0).

and not

let w = x + y, then let u = z2, then let A = w × u.

Wewillsoonintroducesomeconventionsforreducingthe numberof parentheses

Thelatter notation would be tiring and cumbersome to manipulate. in such expressions.

The lambda calculus extends the idea of an expression language to include func-

tions. Where we normally write 1.3 Untypedvs.typed lambda-calculi

2

Let f be the function x 7→ x . Then consider A = f(5), Wehavealready mentioned that, when considering “functions as rules”, it is not

always necessary to know the domain and codomain of a function ahead of time.

in the lambda calculus we just write Thesimplestexampleistheidentityfunctionf = λx.x, whichcanhaveanysetX

2 as its domain and codomain, as long as domain and codomain are equal. We say

A=(λx.x )(5). that f has the type X → X. Another exampleis the function g = λf.λx.f(f(x))

2 2 that we encountered above. One can check that g maps any function f : X → X

Theexpressionλx.x standsforthefunctionthatmapsxtox (asopposedto the to a function g(f) : X → X. In this case, we say that the type of g is

2

statement that x is being mapped to x ). As in arithmetic, we use parentheses to

groupterms. (X →X)→(X→X).

2

It is understood that the variable x is a local variable in the term λx.x . Thus, it

does not make any difference if we write λy.y2 instead. A local variable is also Bybeingflexibleaboutdomainsand codomains,we are able to manipulate func-

called a bound variable. tions in ways that would not be possible in ordinary mathematics. For instance, if

f =λx.xistheidentityfunction,thenwe havef(x) = xforanyx. Inparticular,

One advantage of the lambda notation is that it allows us to easily talk about wecantakex=f,andweget

higher-orderfunctions, i.e., functions whose inputs and/or outputs are themselves

functions. An example is the operation f 7→ f ◦ f in mathematics, which takes a f(f) = (λx.x)(f) = f.

2 3

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.