230x Filetype PDF File size 0.81 MB Source: lllnutrition.com

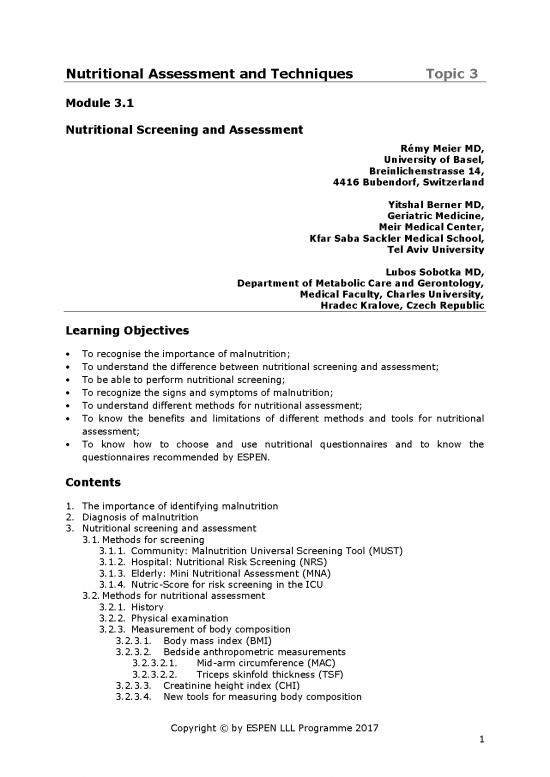

Nutritional Assessment and Techniques Topic 3

Module 3.1

Nutritional Screening and Assessment

Rémy Meier MD,

University of Basel,

Breinlichenstrasse 14,

4416 Bubendorf, Switzerland

Yitshal Berner MD,

Geriatric Medicine,

Meir Medical Center,

Kfar Saba Sackler Medical School,

Tel Aviv University

Lubos Sobotka MD,

Department of Metabolic Care and Gerontology,

Medical Faculty, Charles University,

Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic

Learning Objectives

To recognise the importance of malnutrition;

To understand the difference between nutritional screening and assessment;

To be able to perform nutritional screening;

To recognize the signs and symptoms of malnutrition;

To understand different methods for nutritional assessment;

To know the benefits and limitations of different methods and tools for nutritional

assessment;

To know how to choose and use nutritional questionnaires and to know the

questionnaires recommended by ESPEN.

Contents

1. The importance of identifying malnutrition

2. Diagnosis of malnutrition

3. Nutritional screening and assessment

3.1. Methods for screening

3.1.1. Community: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)

3.1.2. Hospital: Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS)

3.1.3. Elderly: Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA)

3.1.4. Nutric-Score for risk screening in the ICU

3.2. Methods for nutritional assessment

3.2.1. History

3.2.2. Physical examination

3.2.3. Measurement of body composition

3.2.3.1. Body mass index (BMI)

3.2.3.2. Bedside anthropometric measurements

3.2.3.2.1. Mid-arm circumference (MAC)

3.2.3.2.2. Triceps skinfold thickness (TSF)

3.2.3.3. Creatinine height index (CHI)

3.2.3.4. New tools for measuring body composition

Copyright © by ESPEN LLL Programme 2017 1

3.2.3.5. Nitrogen balance

3.2.4. Measurement of inflammation

3.2.5. Measurement of function

3.2.5.1. Muscle strength

3.2.5.2. Cognitive function

3.2.5.3. Immune function

3.2.5.4. Quality of life assessment (QoL)

4. Assessment of food intake and nutritional questionnaires

5. Summary

6. References

Key Messages

Patients with nutritional risks are frequently seen in clinical practice;

Nutritional screening and assessment are important parts of patient care;

Nutritional screening and assessment identify patients at nutritional risk and those

requiring nutritional support;

Nutritional screening is a rapid and simple tool and should be done in every patient;

Nutritional assessment is important for detailed diagnosis of acute and chronic

malnutrition;

Food intake should be evaluated in all patients at risk of malnutrition.

Copyright © by ESPEN LLL Programme 2017 2

1. The Importance of Identifying Malnutrition

Nutrition is a basic requirement for life. Accordingly nutrition plays an important role in

promoting health and preventing disease. Many factors can lead to weight change and

malnutrition. Malnutrition is a condition resulting from a combination of varying degrees

of under- or overnutrition and inflammatory activity, leading to an abnormal body

composition and diminished function (1). Several classifications of malnutrition have

been proposed in the past. Even now there is still no universally accepted definition.

Patients with minor nutritional deficiencies and those with overt under- or overnutrition

are common in clinical practice. The prevalence of malnutrition (undernutrition) among

hospitalized adult patients ranges from 30 to 50%, depending on the criteria used, and in

part whether those at high risk as well as those with established malnutrition are

included (2, 3). The EuroOOPS study from 12 European countries, which included data

from 26 hospital departments, found that 32.6% of the patients were at risk for

undernutrition (4). Undernutrition should be seen as an additional disease, as well as an

important component of comorbidity. The underlying condition and inadequate provision

of nutrients (particularly energy and protein) are the main reasons for developing

undernutrition. Many patients are already undernourished before they reach the hospital.

Those at highest risk for undernutrition are older people who are hospitalized or living in

care homes, people on low incomes or who are socially isolated, people with chronic

disorders, and those recovering from a serious illness or condition, particularly a

condition that affects their ability to eat. In addition, hospitalized patients often show

further deterioration in their nutritional status. One large survey showed that four out of

five patients do not consume enough to cover their energy or protein needs (5). There

are many known reasons to explain this. The underlying disease may directly impair

nutrition (as, for example, in the case of an oesophageal stricture) and can induce

metabolic and/or psychological disorders which increase the nutritional needs or decrease

food intake. In addition, the fasting periods before many examinations and interventions

lead to further inadequate food intake. Hospital undernutrition can also become

aggravated because of inappropriate meal services, inadequate quality and flexibility of

the hospital catering, and insufficient aid provided by the care staff.

The consequences of undernutrition are well-known. A poor nutritional status leads to an

increase in complications, a longer length of stay, higher mortality, higher costs and

more re-admissions (4, 6). The EuroOOPS study, for example, found significant increases

in complications, length of stay and mortality in patients at risk for undernutrition (4).

Undernutrition also influences the efficacy or tolerance of several key treatments, such as

antibiotic therapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery. Furthermore, it is now clearly

demonstrated that undernutrition significantly increases overall health care costs (7).

Undernutrition is undoubtedly a major burden for patients and health care professionals,

and routinely should be actively sought. When undernutrition is diagnosed, it should be

treated in accordance with an individual nutritional care plan. The best outcomes are

seen when there is supervision by a multidisciplinary nutritional support team.

To improve the overall outcomes from nutritional treatment it is necessary to select

patients with overt undernutrition/malnutrition, and those at most risk of developing

nutritional deficiencies during their hospitalization. An ideal care plan should start by

screening all patients when they are admitted, proceeding to a detailed assessment of

nutritional status in those found to be at increased risk. In patients who are identified to

be malnourished or at high risk, an appropriate nutritional intervention should follow.

Unfortunately, although this process is well-known and forms part of several national and

international guidelines, it is not carried out everywhere. It remains necessary to raise

Copyright © by ESPEN LLL Programme 2017 3

awareness of undernutrition and to improve the outcomes of patients’ treatments by

nutritional measures.

2. Diagnosis of Malnutrition

Because of the lack of a general definition of malnutrition, ESPEN has started a process

for the diagnosis of malnutrition. In a Delphi process, an expert group assigned by ESPEN

has given consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis of malnutrition that

should be applied independent of clinical setting and aetiology of the condition (8).

There are two options for the diagnosis of malnutrition (Table 1). Option one requires

2

body mass index (BMI, kg/m ) <18.5 to define malnutrition. This criterion is in

accordance with the traditional definition of underweight as recommended by the WHO.

Option two requires the combined finding of involuntary weight loss (mandatory) and at

least one of either reduced BMI or a low fat free mass index (FFMI). Weight loss could be

either >10% of habitual weight indefinite of time, or >5% over 3 months. Reduced BMI

2

is <20 or <22 kg/m in subjects younger and older than 70 years, respectively. Low FFMI

2

is <15 and <17 kg/m in females and males, respectively (9).

Table 1

Ways to diagnose malnutrition

Alternative 1:

2

BMI <18.5 kg/m

Alternative 2:

Weight loss (involuntary) >10% indefinite of time, or >5% over the last 3 months

combined with either

2 2

BMI <20 kg/m if <70 years of age, or <22 kg/m if ≥70 years of age

or

FFMI <15 and 17 kg/m2 in women and men, respectively.

3. Nutritional Screening and Assessment

Screening and assessment tools have been developed to facilitate early recognition of

malnutrition in all patients.

All patients should have their nutritional status recorded. Evaluation starts with a

screening procedure and is followed by a detailed assessment in those patients screened

and found to be at risk (10, 11).

Nutrition screening is a tool for rapid and simple evaluation of patients at risk of

undernutrition (Fig. 1).

Copyright © by ESPEN LLL Programme 2017 4

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.