166x Filetype PDF File size 1.98 MB Source: digilib.uns.ac.id

82

ppeerrppuuststaakakaaann..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd ddiiggiilliibb..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd

CHAPTER IV

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Results of the Research

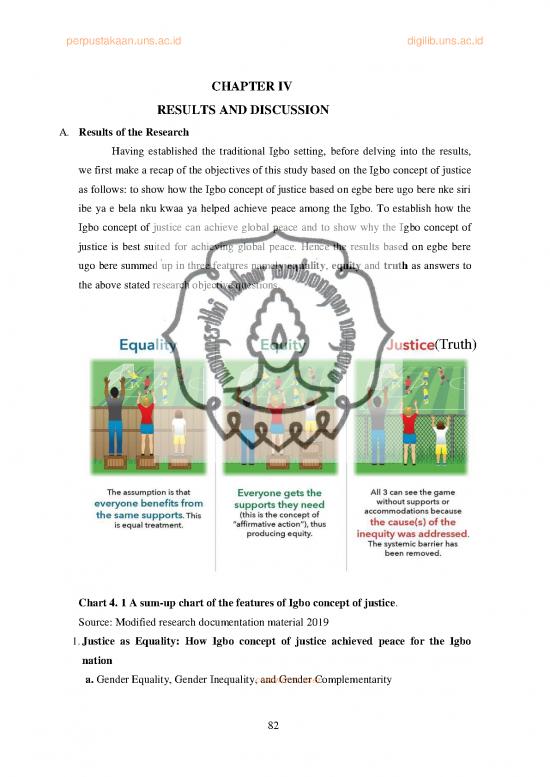

Having established the traditional Igbo setting, before delving into the results,

we first make a recap of the objectives of this study based on the Igbo concept of justice

as follows: to show how the Igbo concept of justice based on egbe bere ugo bere nke siri

ibe ya e bela nku kwaa ya helped achieve peace among the Igbo. To establish how the

Igbo concept of justice can achieve global peace and to show why the Igbo concept of

justice is best suited for achieving global peace. Hence the results based on egbe bere

ugo bere summed up in three features namely equality, equity and truth as answers to

the above stated research objective questions.

(Truth)

Chart 4. 1 A sum-up chart of the features of Igbo concept of justice.

Source: Modified research documentation material 2019

1. Justice as Equality: How Igbo concept of justice achieved peace for the Igbo

nation

a. Gender Equality, Gender Inequality, and Gender Complementarity

ccoommmmiitt ttoo uusserer

82

83

ppeerrppuuststaakakaaann..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd ddiiggiilliibb..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd

Contextually, equality is defined here as giving no preferential treatment to

anyone based on racial, ethnic, religious, sexual or any other such consideration.

Besides race, ethnicity and religion, gender is one big issue in matters of equality which

brings chaos and denies people of peace in most cases. Igbo concept of justice looks at

equality from the aspects of race, ethnicity, religion and then gender. Democracy and

democratic ethos are also highlighted and faithfully followed unlike what obtains in

Christian/Western concept. The Igbo proverb that comprehensively captures their sense

of equality in justice is e kebe oke n’aka n’aka a mara ndị a hụrụ n’anya (when things

are shared individually/per hand, the favoured one is known). This goes to show the

people’s innate aversion to injustice and perception of all humans as equal.

On gender equality, the patriarchal societal arrangement has been usually

associated with Ndịgbo especially by the Euro-American literature from time

immemorial. For reason of organisational structure and maintaining of family lineage,

some things are handled by men. However, this does not mean a relegation of the

womenfolk to the background for as Ndịgbo believe, all people, whether man or woman

are intrinsically equal and should be treated equally not only before the law but also in

other matters of life including rulership as in Igbo chiefdoms.

The first informant Odo who also doubles as supporting informant, is a male,

aged 50. Graduate and lecturer, he agrees strongly that there is a strong sense of equality

in Igbo concept of justice than in its Christian/Western counterpart. From his experience

as a lecturer in the higher institution with students from different ethnic nationalists, he

argues that the Igbo are known to not only protect the interests of the womenfolk but do

not mind sharing equal responsibilities and privilges with the latter even in class

activities. This informant equally agrees that a leader’s powers are impotent if such

powers are unjust and so cannot guarantee peace. He also strongly agrees that there was

more sense of justice among the Igbo pre-Christian era. The interviewee who also

agrees that the leaders were more just and less corrupt before the Christian/Western

corruption of the Igbo concept of justice based on egbe bere ugo bere. While

acknowledging the inadequacies of Igbo concept of justice especially on the grounds of

such cultural practices like killing of twins which unjustly denied infants the

opportunity to live, this interviewee advocated the adoption of Igbo concept of justice

with a tint of the western/Christian version that avoids such heinous practices like the

ccoommmmiitt ttoo uusserer

84

ppeerrppuuststaakakaaann..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd ddiiggiilliibb..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd

killing of twins. This is also the stance of other informants namely, Asọgwa, Asọnye,

Mgbeorie, Ọyịma and Ezeokorie.

But centrally, gender equality is a given for Ndịgbo. According to the seventh

informant, Nneka, Igbo culture recognises women as equal entities to men but [only] of

a different specie. This view is very averse to the western notion and practice of gender

equality. Nneka explained that, that is why female chiefs are equally celebrated and

respected in Igboland. As shown in the chart above, just like the family watching

football game, the equality feature of Igbo justice ensures that everyone is given equal

opportunity to achieve their aims. This is unlike what obtains in the

global/western/Christian concept which though defines equality in same notion but

practices it in opposite direction. On March 28 this year, the US Women soccer team

instituted legal proceedings against the country’s soccer (football) association seeking

for equal pay with their men counterparts. While the women’s team are four-time

winners of the women’s world cup having won it back to back this July, their men

counterparts have not only never won the world cup but are one of the lowest ranked in

the world.

Yet, the latter receive 72 percent higher pay than the former. In short, had the

men been the winners of the world cup they were to receive about one million dollars

each but the actual winners of the France 2019 world cup, the women can only hope for

two hundred and fifty thousand dollar match pay. There are many other agonising

instances of gender inequality just as it abounds in most countries including Nigeria but

suffice it to say that this is just a tip of the iceberg in the chasm of gender inequality

perpetrated and promoted by the global Christian West to the detriment of the

womenfolk.

In Anioma– the Igbo area west of the River Niger – there is a firmly established female

chieftaincy institution dating roughly to the end of the fifteenth century. As Nneoma,

the eight informant observed, until 1990, female chiefs in Anioma called Omu were

very old women knowledgeable in the traditions of their people, and charged with

certain ritual and secular duties. This according to Uchendu (2006) is why the Igbo

concept of justice trumps above the west.

Anioma boasts of political systems fashioned after the monarchical system

ccoommmmiitt ttoo uusserer

borrowed from the ancient Benin and Igala kingdoms, the patrilineal kinship system of

85

ppeerrppuuststaakakaaann..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd ddiiggiilliibb..uunns.s.aac.c.iidd

the Igbo heartland, and a combination of both. However, while male monarchs, male

title-holders and male elders were in control of local politics, women, generally, had

little obvious political function before and during the colonial period.

For the informants, Mgbeafọ, Ezeọba, Anịkwenwa and Chukwudị, the Aniocha section

of Anioma, however, hosts the ụmụ ezechima, some nine towns that trace their roots to

Benin. Pre-colonial ụmụ ezechima had a female chieftaincy institution with female

chiefs called Omu who supervised female affairs and represented women in local

councils that were dominated by men. Each town comprised a host of major lineages

and was entitled to one Omu. No town, therefore, had more than one female

representative in the local governing council. This female presence in local

administration observed in Aniocha in the pre-colonial and colonial periods did not

exist elsewhere in Anịoma.

Like in other Igbo communities, Anioma’s communal leadership in pre-independence

was a male responsibility. But Aniocha female chiefs were largely responsible for

female affairs while men ruled the entire community. The traditional gendered system

of political power is believed to be based on the idea that some aspects of governing

were the appropriate responsibility of women and others were the appropriate

responsibility of men similar to what existed in Western Europe before the nineteenth

century.” (See Uchendu, 2006).

While Engels emphasises economic aspect as being pivotal in the unequal

relationship between men and women, in Igbo traditional society, it is culture that

explains the relationship be it equal, unequal, or complementary. In her theory, Lesser

Blumberg (1984) claims that it is only the production of surplus resources and access to

and control over these resources, that translates into power or valued success—for men

and women alike. Blumberg’s point plays out in Igbo traditional culture. That culture

produced a category of highly resourceful, successful, and economically empowered

women who could take male titles and wielded a lot of influence in their families and

communities.

In buttressing Blumberg’s position, the fifth informant, Ọyịma affirms that what

determine social status in Igboland as in all parts of Africa, are economic power and

hardly gender. According to her, a rich woman, an educated woman or enlightened

woman who is outspoken, hardworking, and fearless can hardly expect to be looked

ccoommmmiitt ttoo uusserer

no reviews yet

Please Login to review.